-

Exposure Management Platform

Complete security visibility across IT, OT, IoT, cloud, mobile, and remote assets.

-

Integrations

runZero seamlessly integrates with a wide variety of tools, enhancing network visibility, enriching asset data, and uncovering control gaps.

-

Community Edition

Our completely free version of the runZero Platform is ideal for home use and environments with fewer than 100 assets.

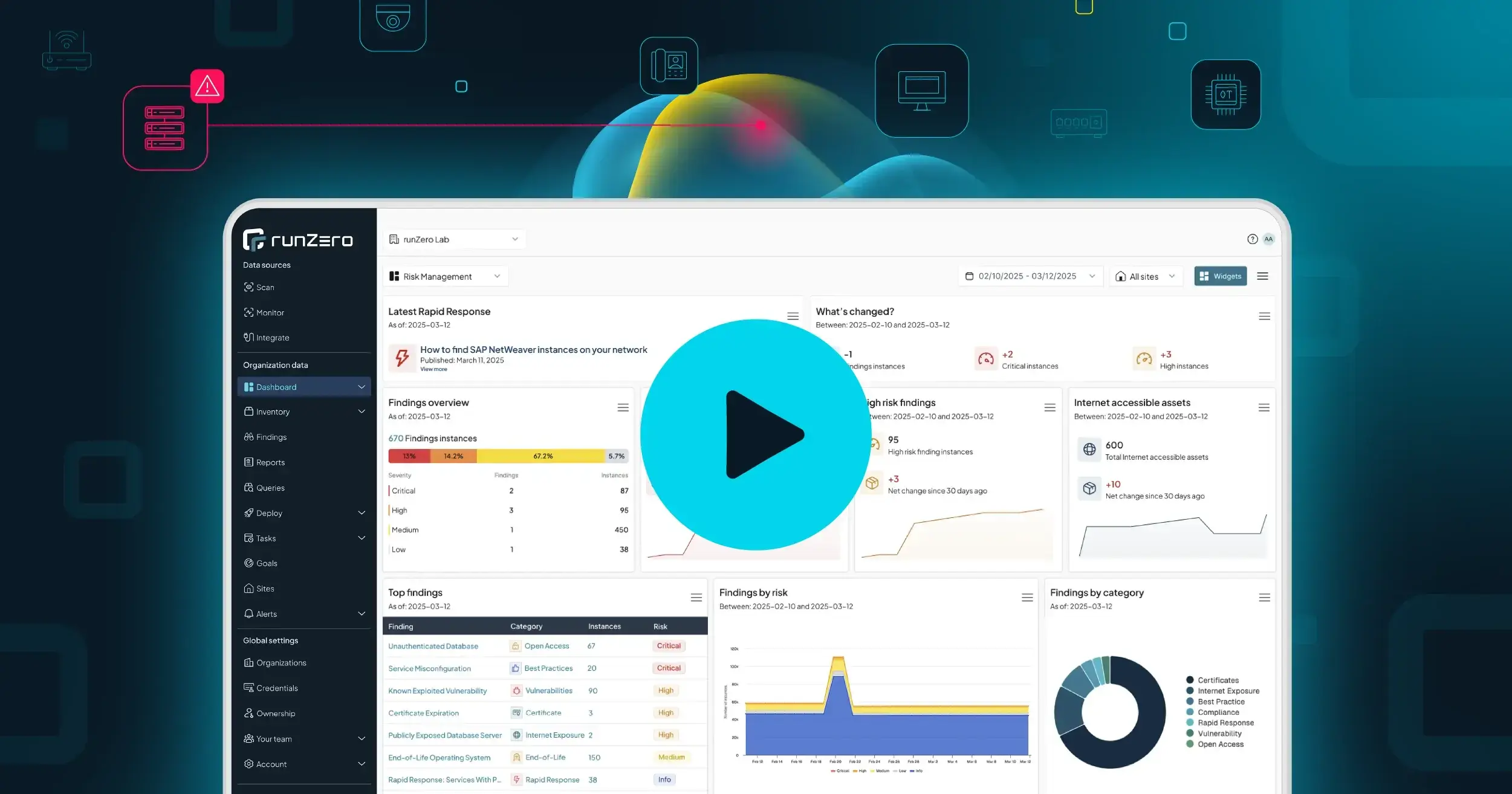

Welcome to the new era of exposure management

Check out our launch video to see how we're fixing what’s broken with vulnerability management & overcoming persistent problems.

-

Solutions

Gain visibility, control the unknowns, and ensure compliance with confidence.

-

Regulatory Compliance

Ensure compliance and stay resilient against evolving cyber threats.

It’s time to move away from legacy vulnerability management

Legacy vulnerability scanners were built for a different time — when networks had clear perimeters, assets were reachable, and credential-based scanning was feasible across the board. That world doesn’t exist anymore.

-

Resource Center

Dive into a treasure trove of resources to expand your exposure management knowledge.

-

runZero Research

Explore the world of exposure management through the runZero lens.

-

runZero Blog

See what's happening at runZero and read up on the latest ideas, opinions, and articles from our experts and researchers.

-

Support Resources

Everything you need to maximize your experience with the runZero Platform.

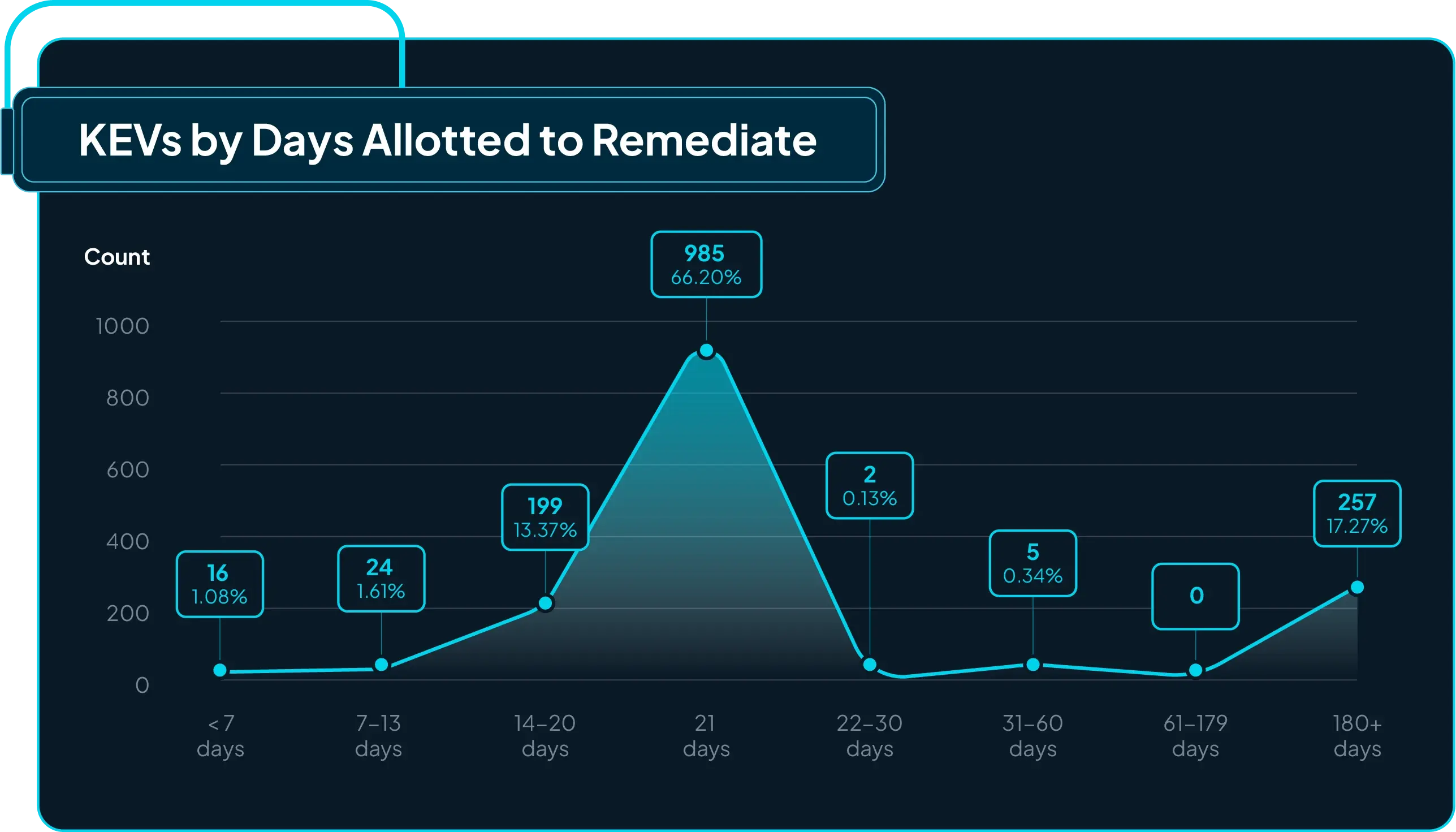

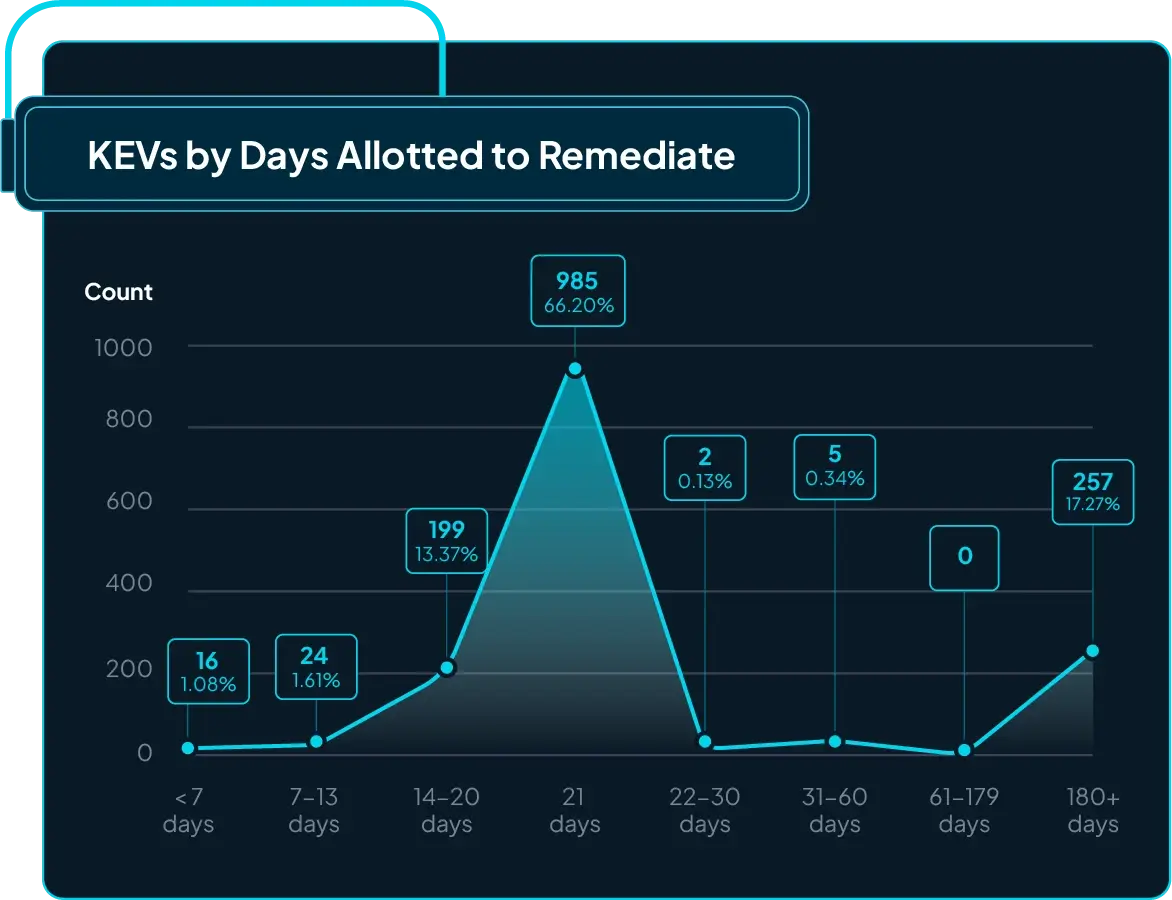

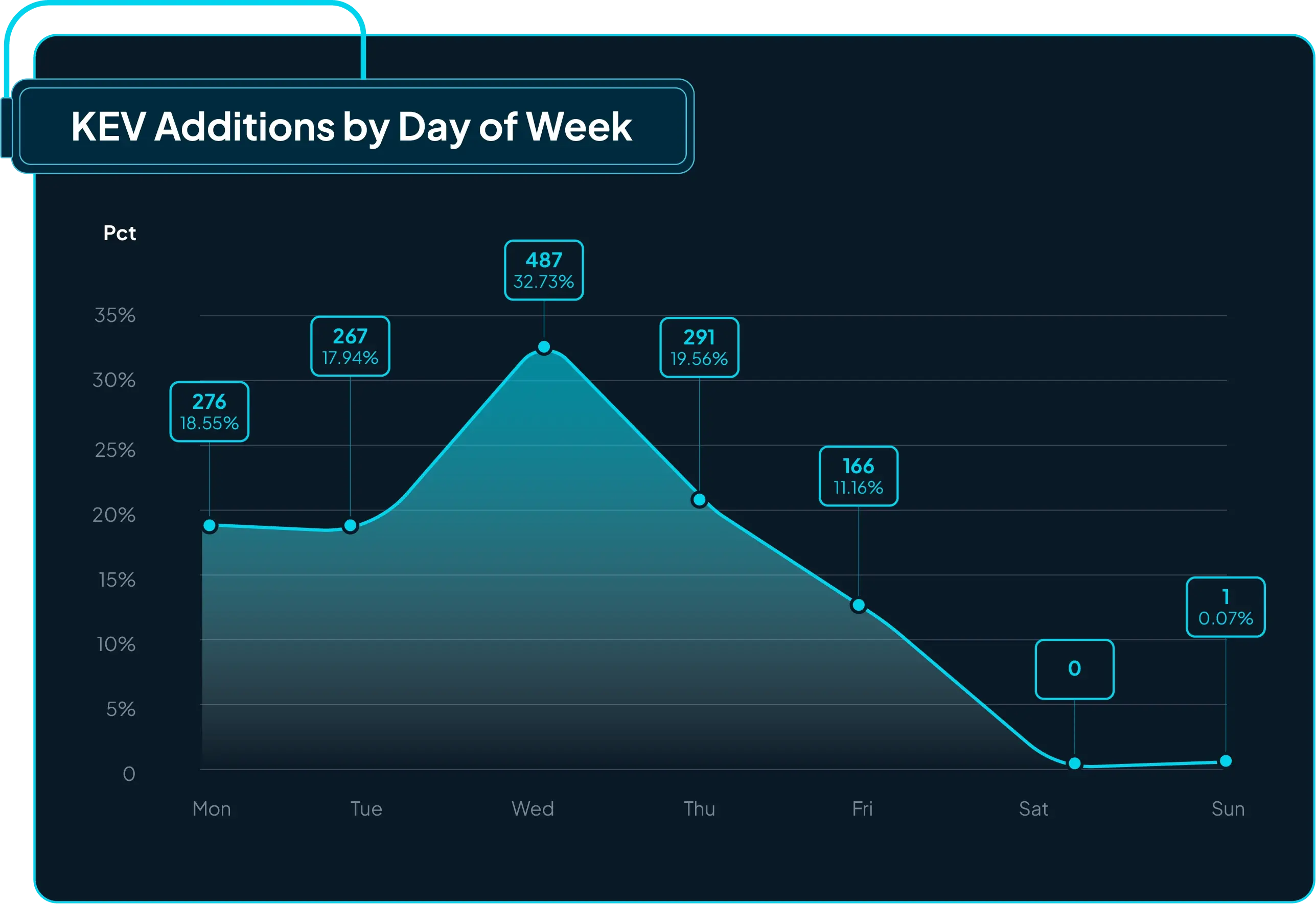

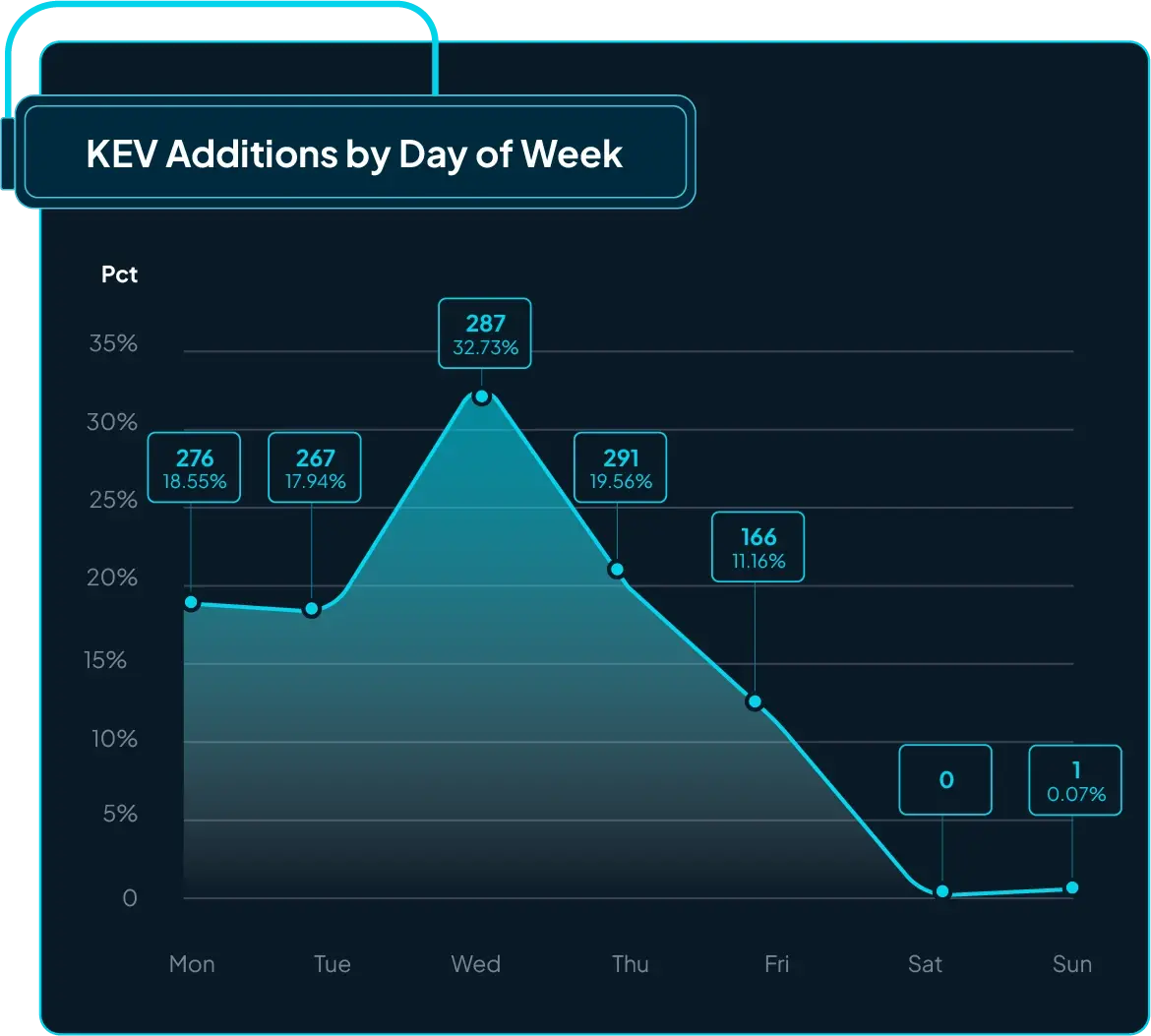

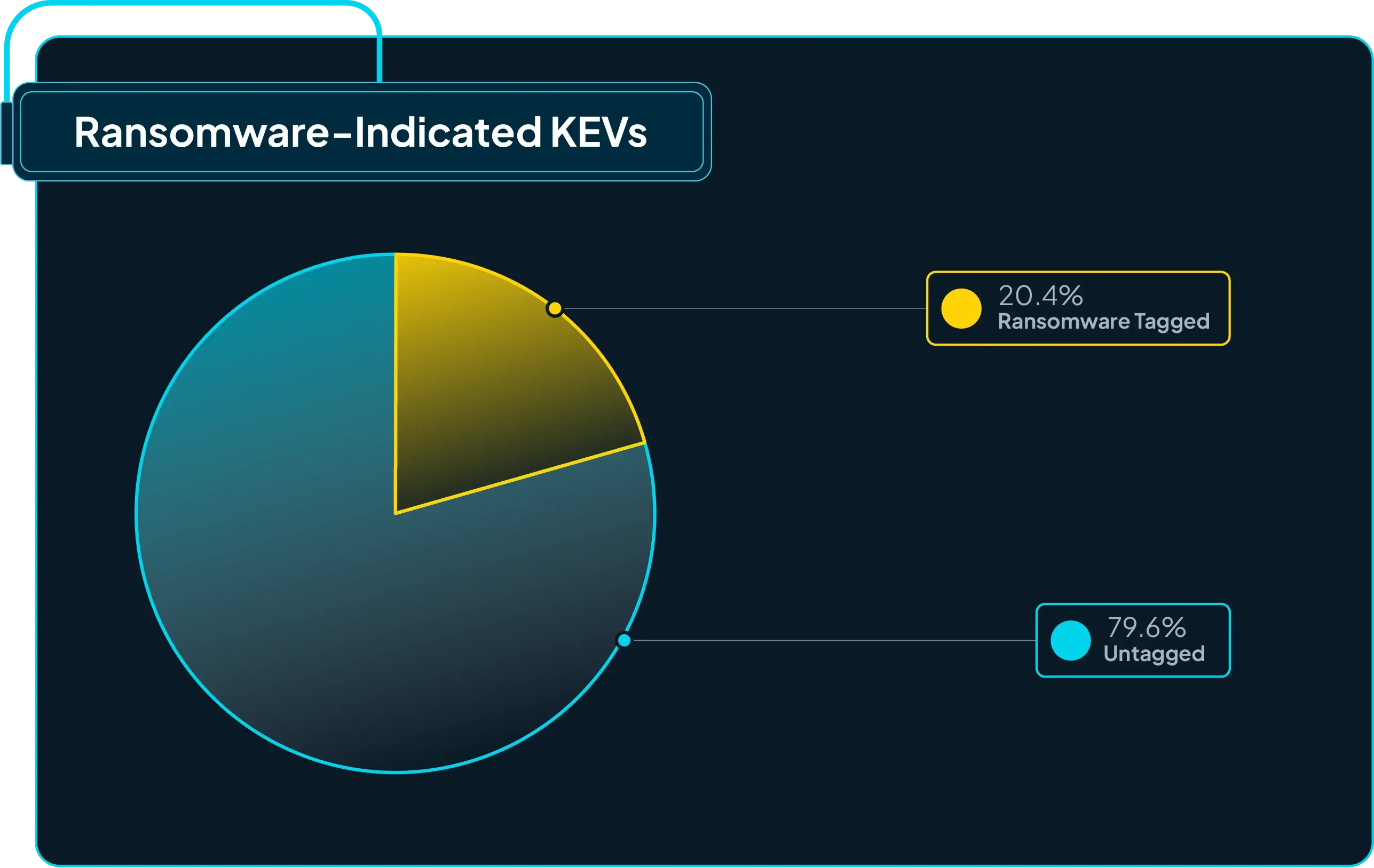

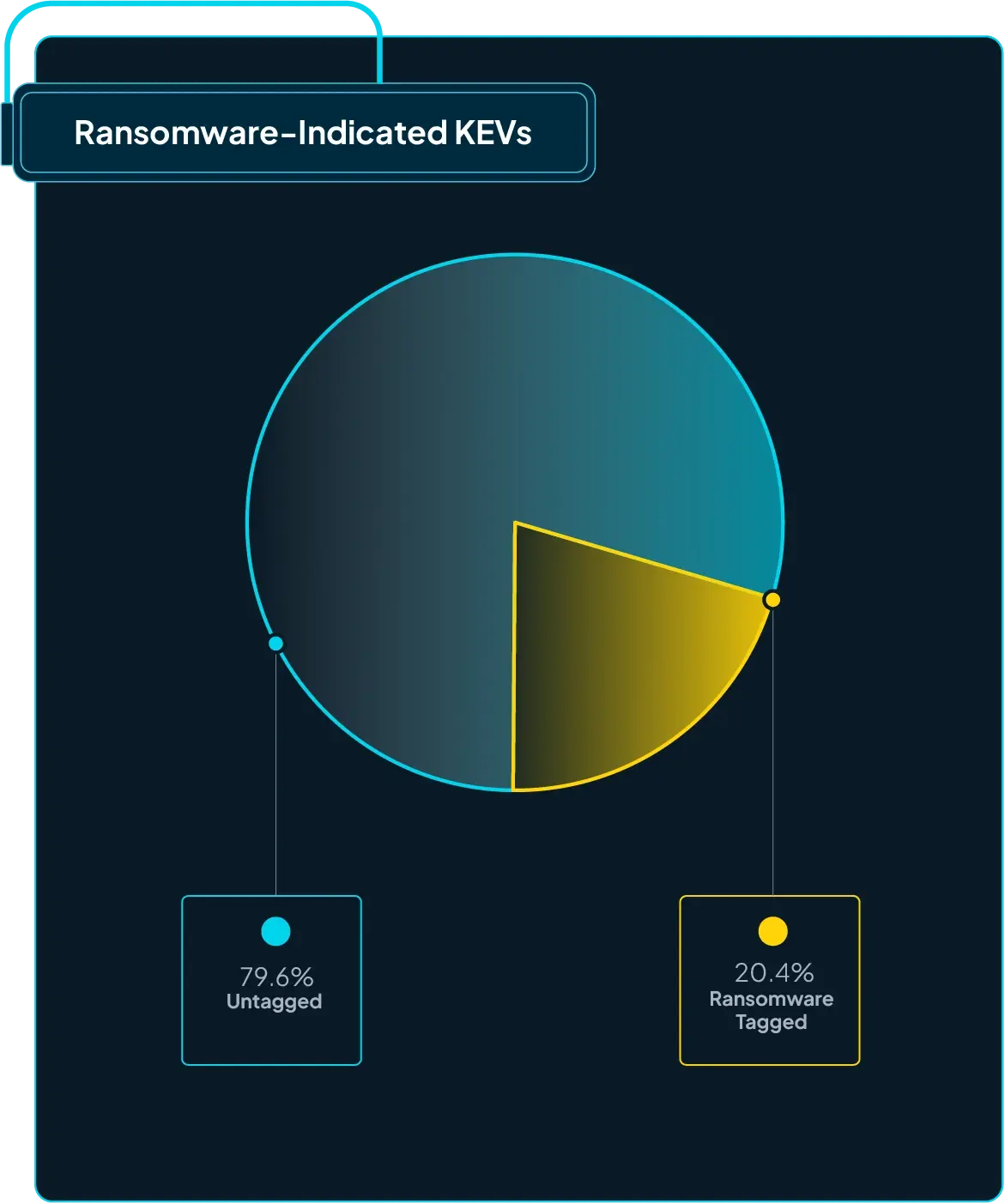

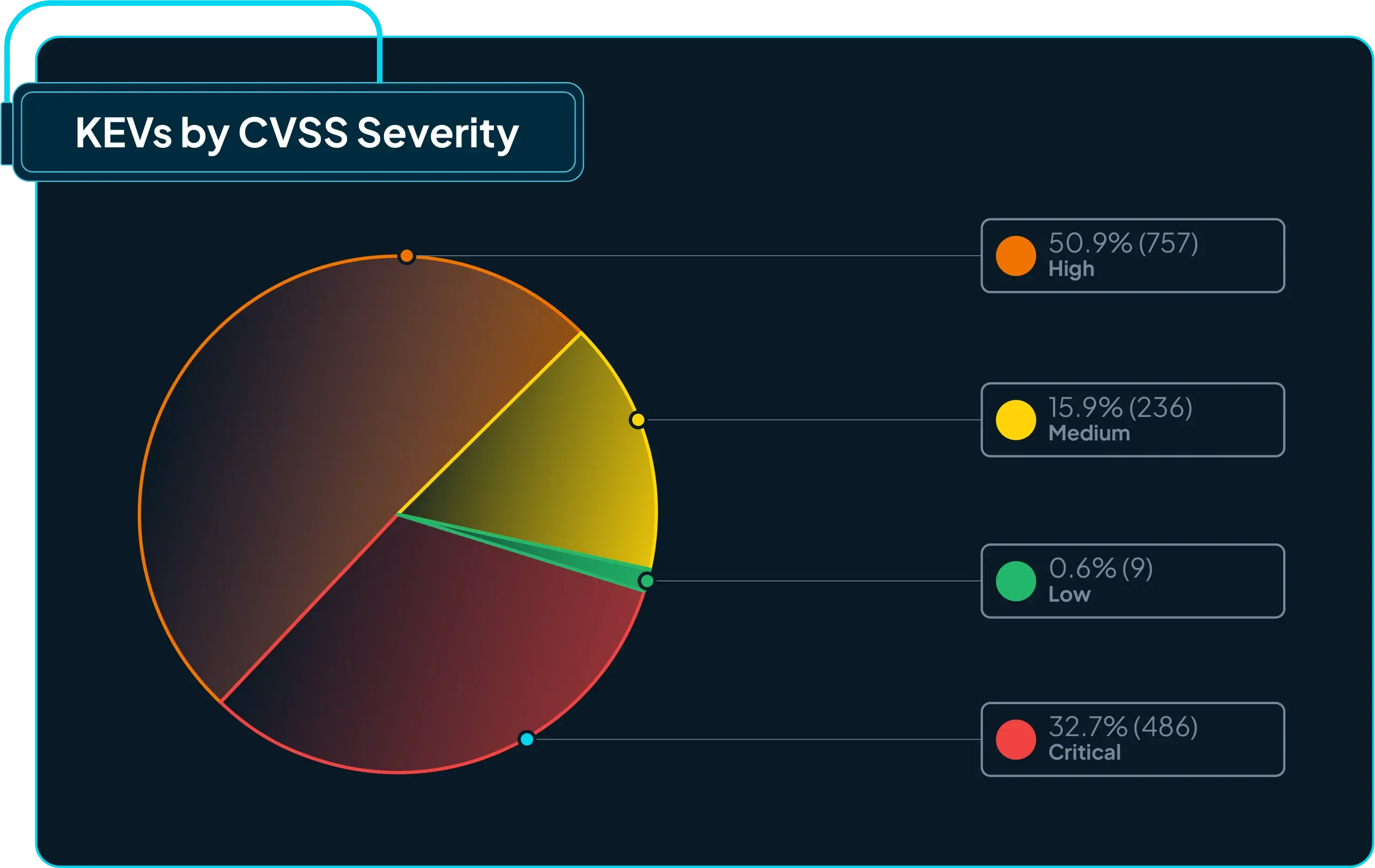

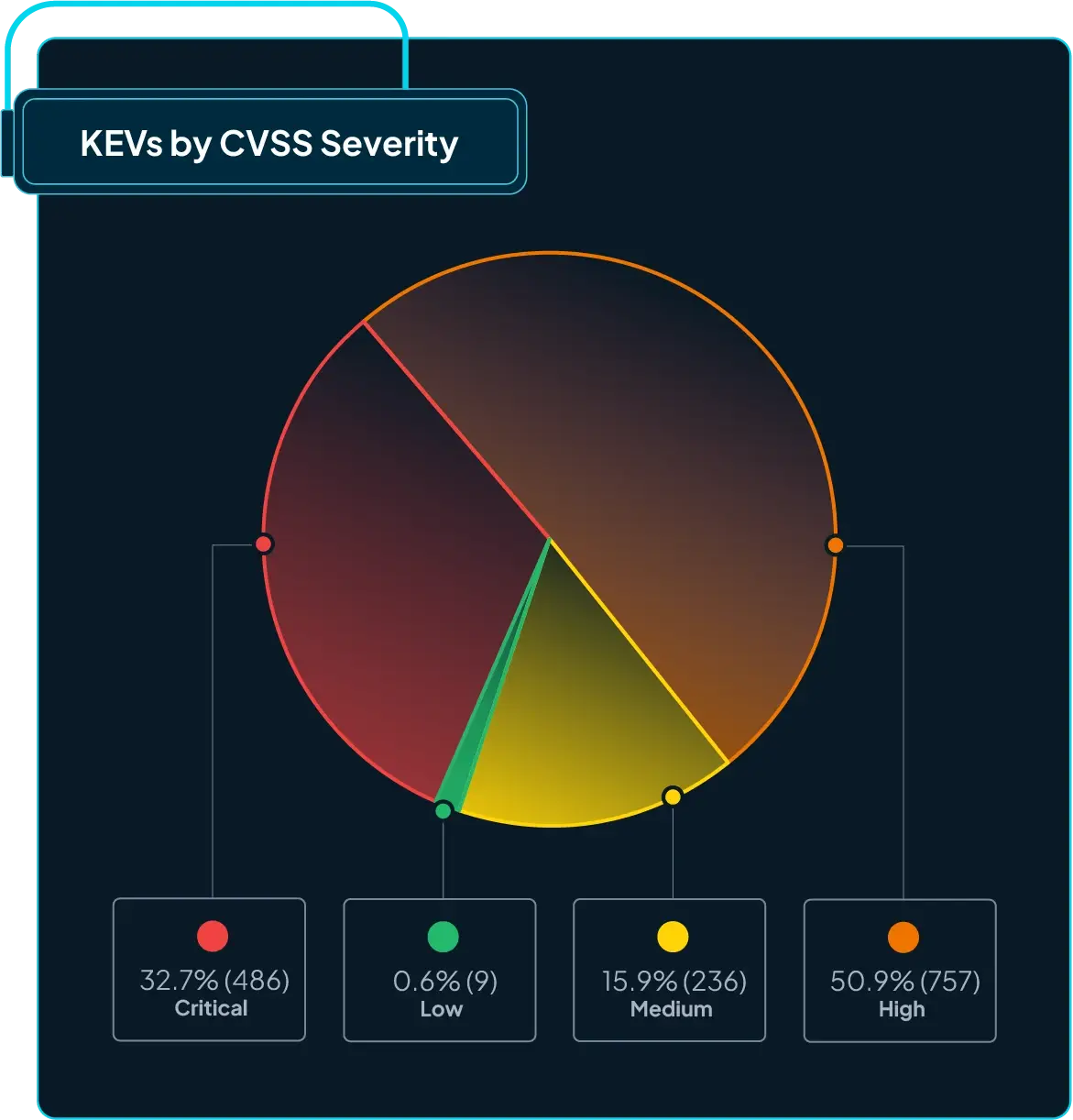

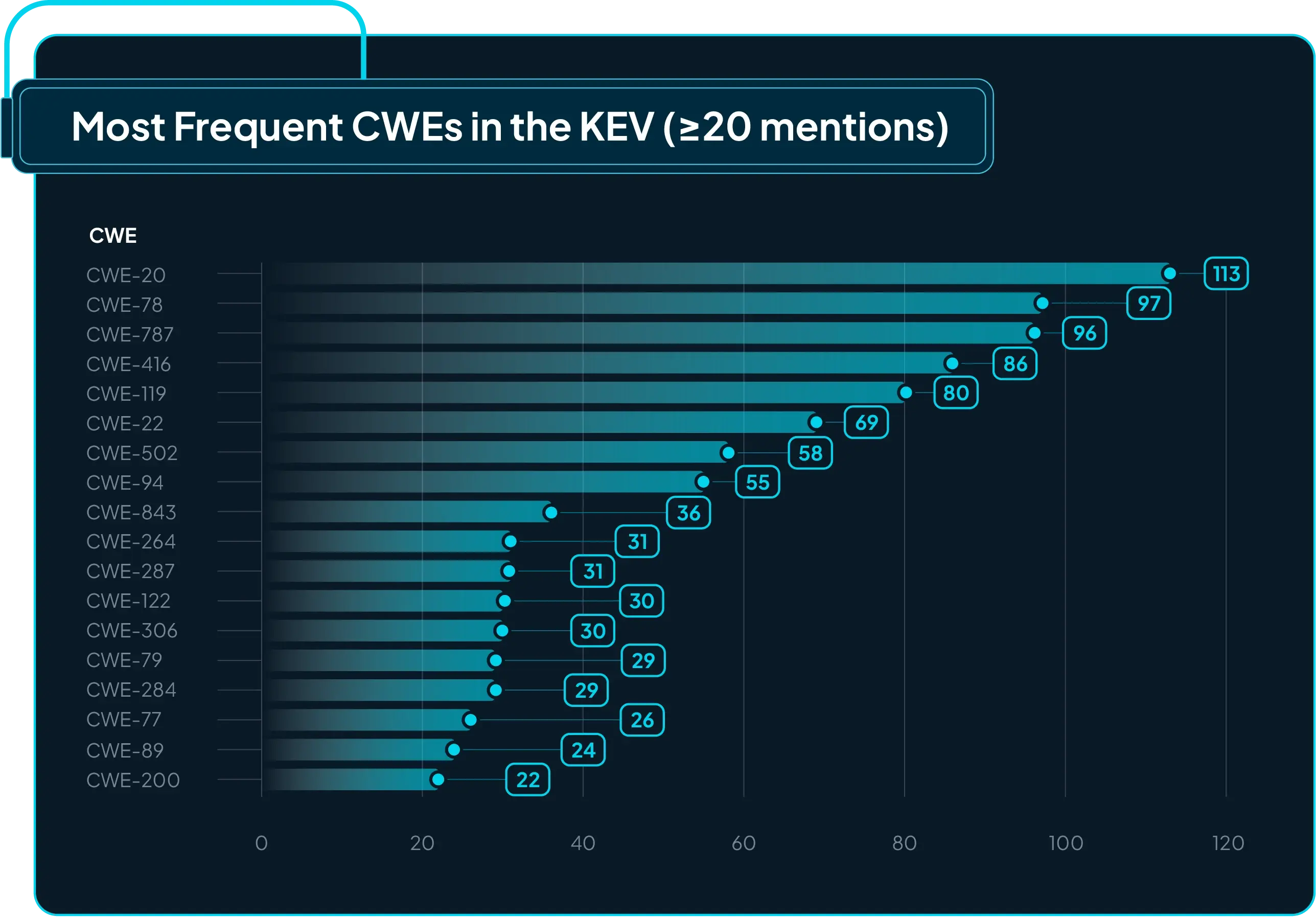

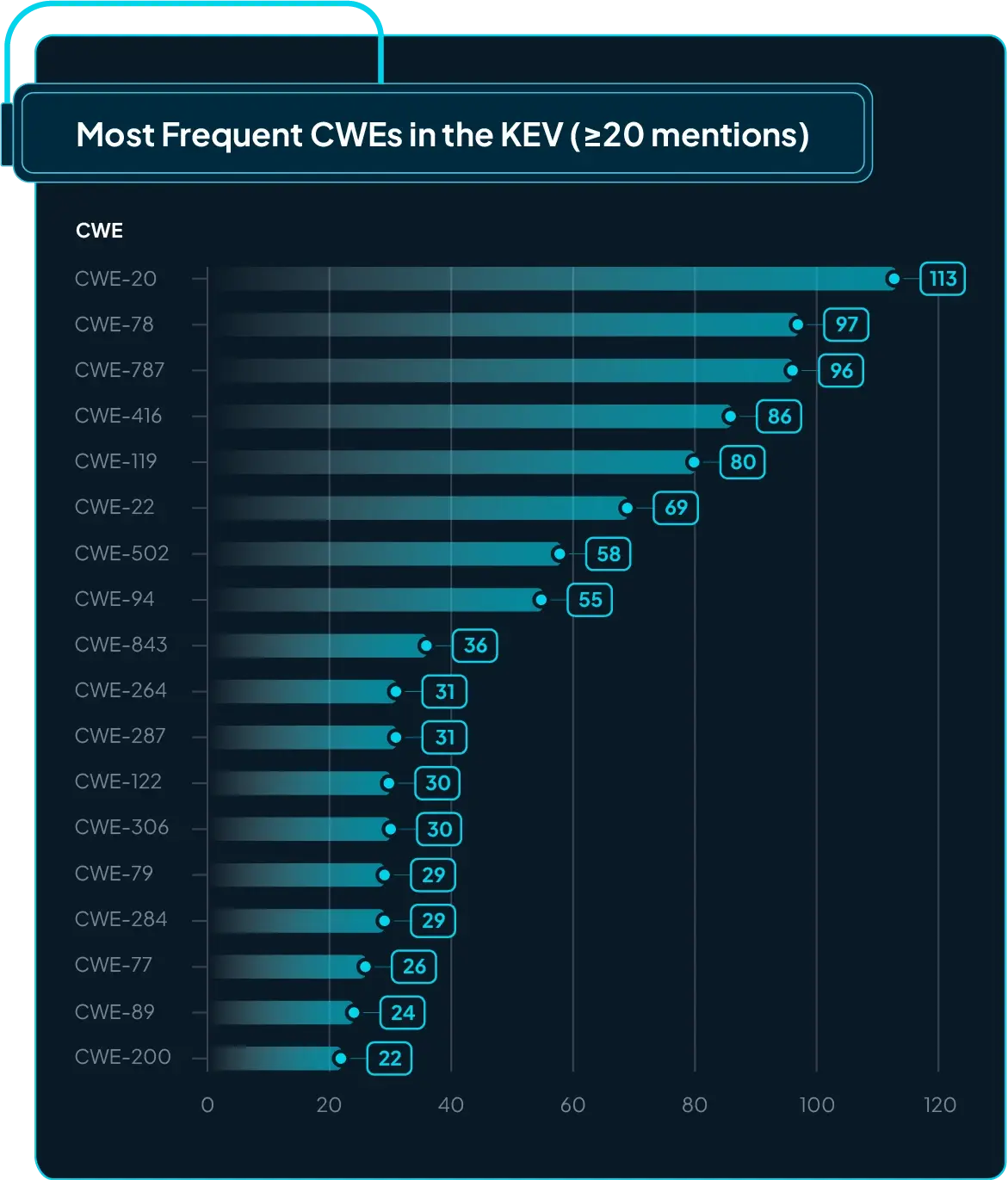

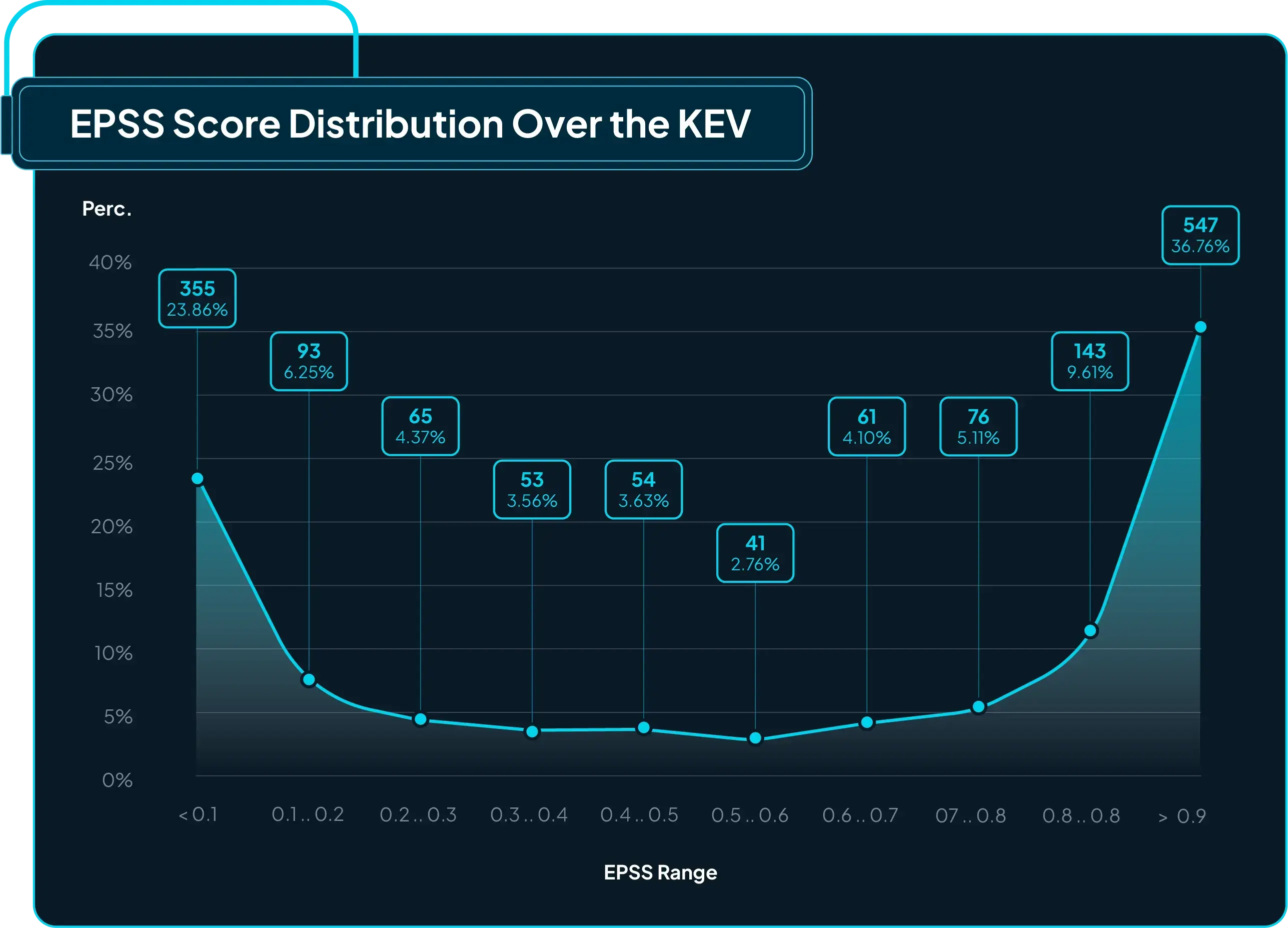

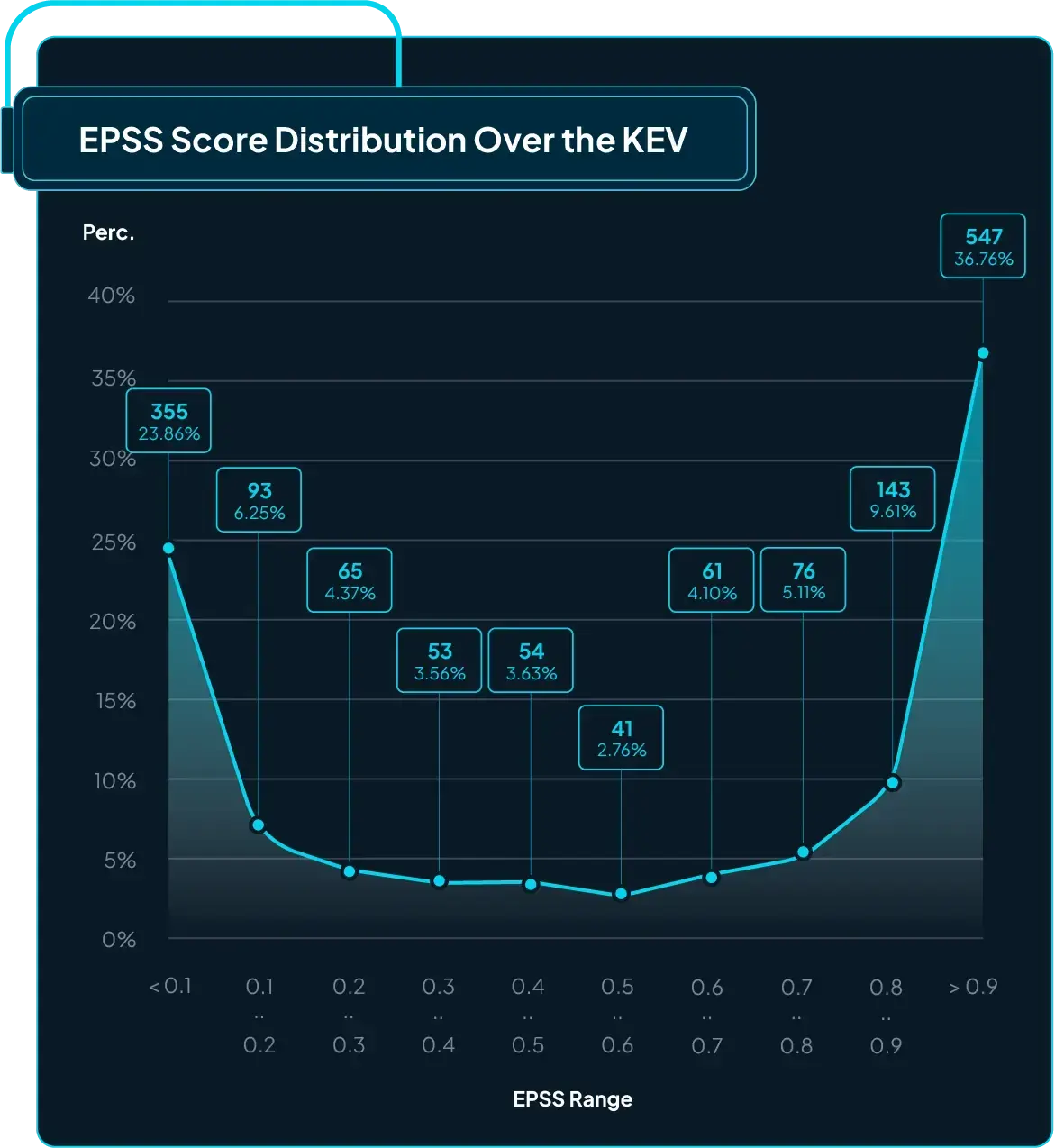

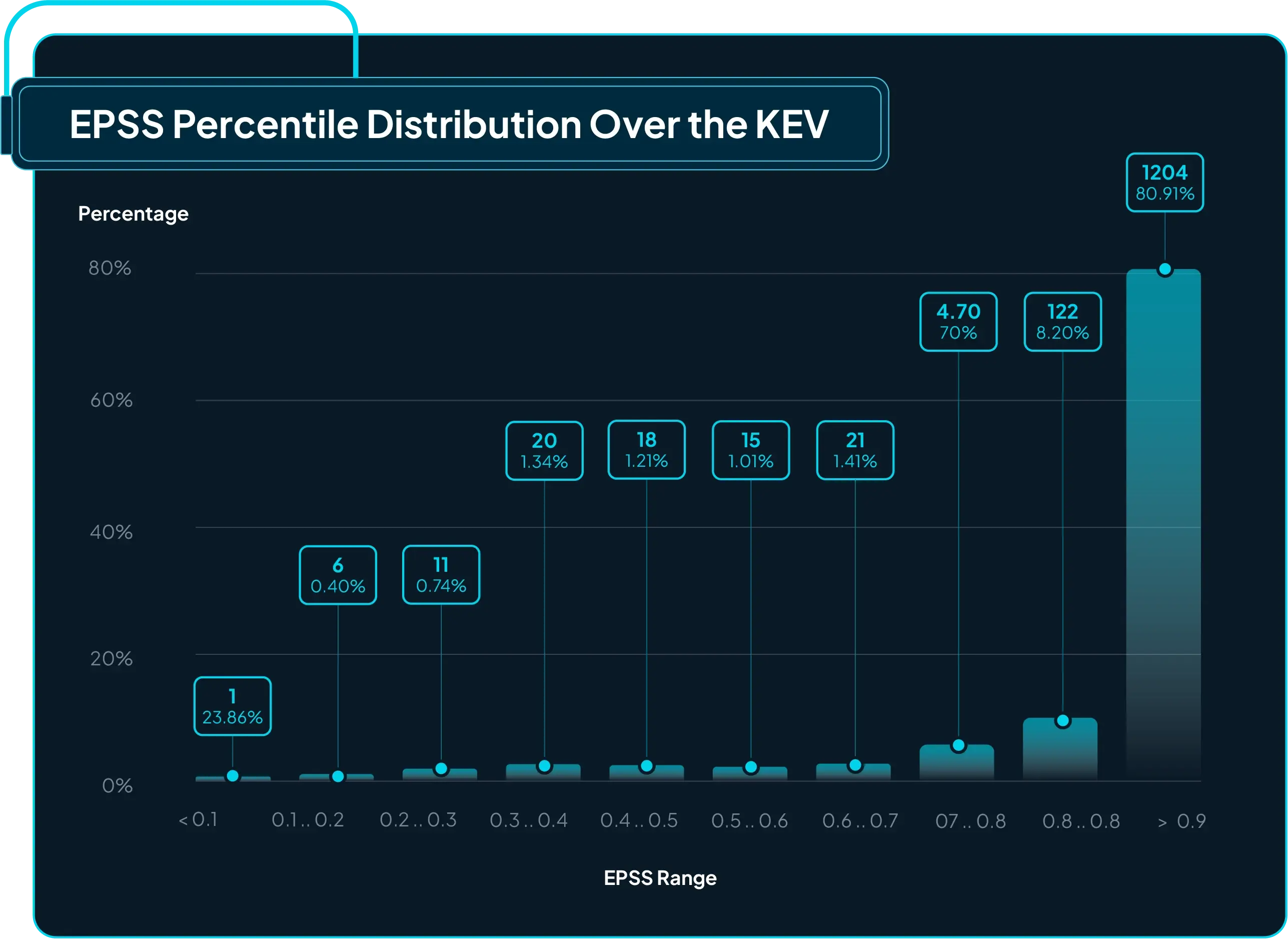

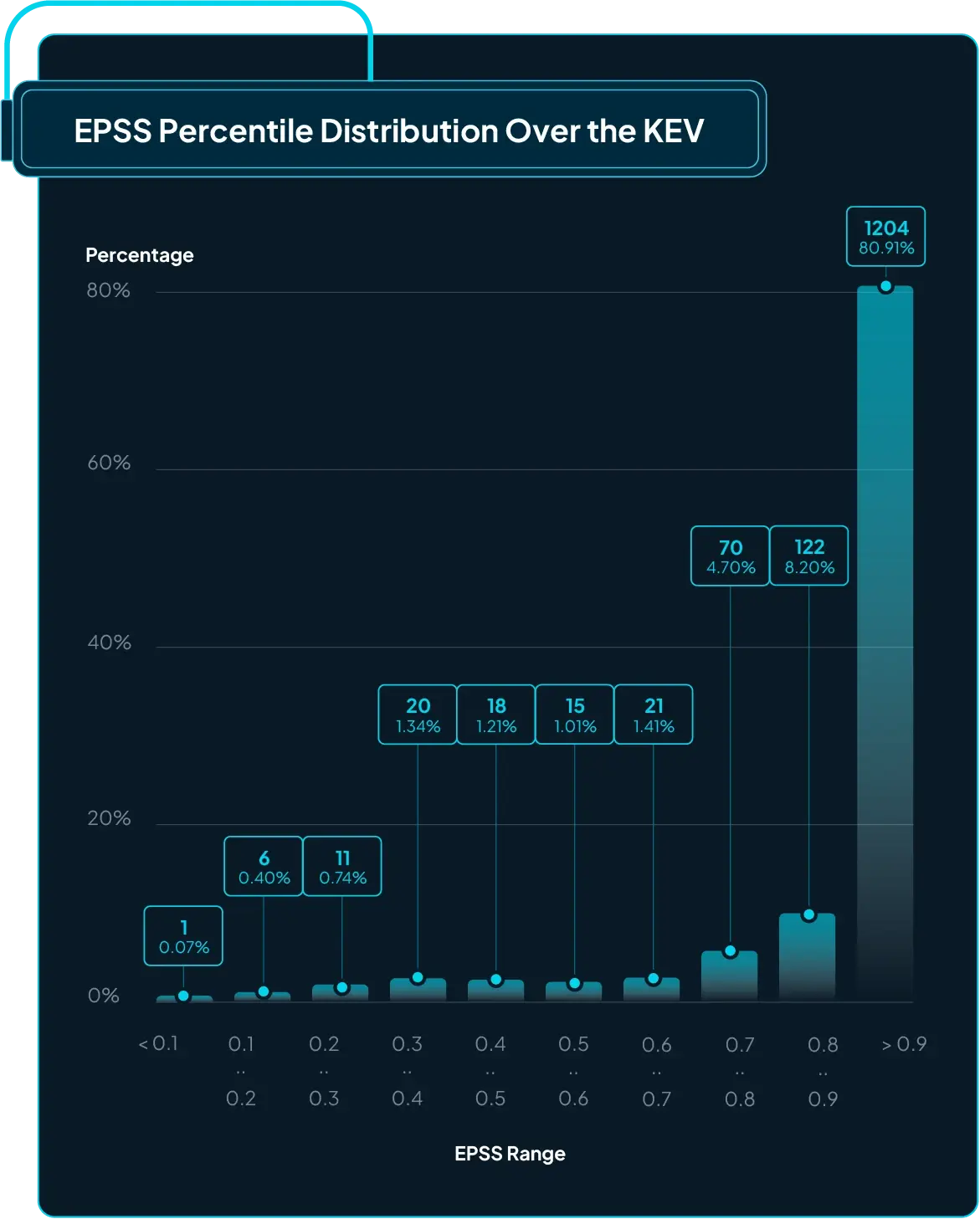

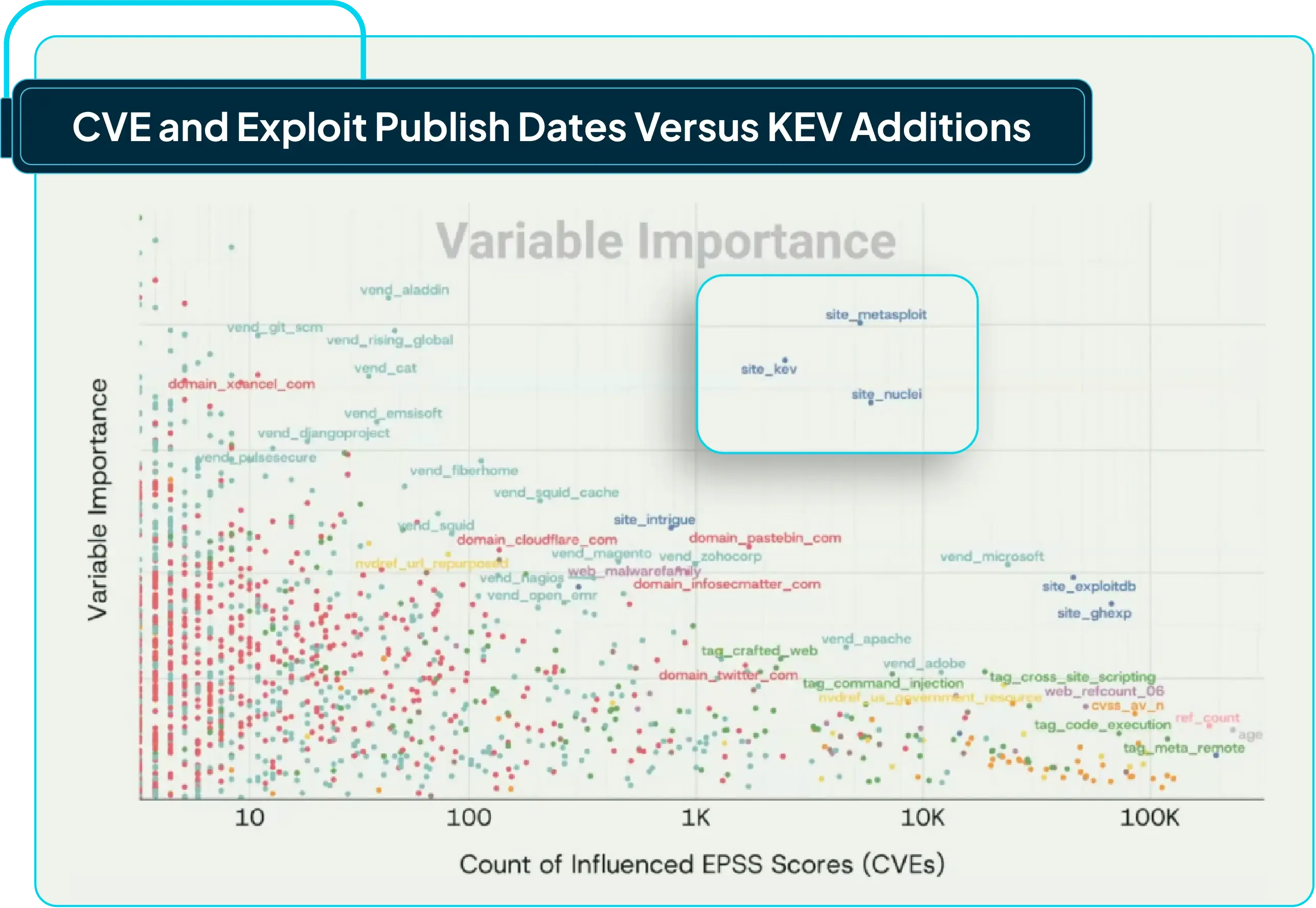

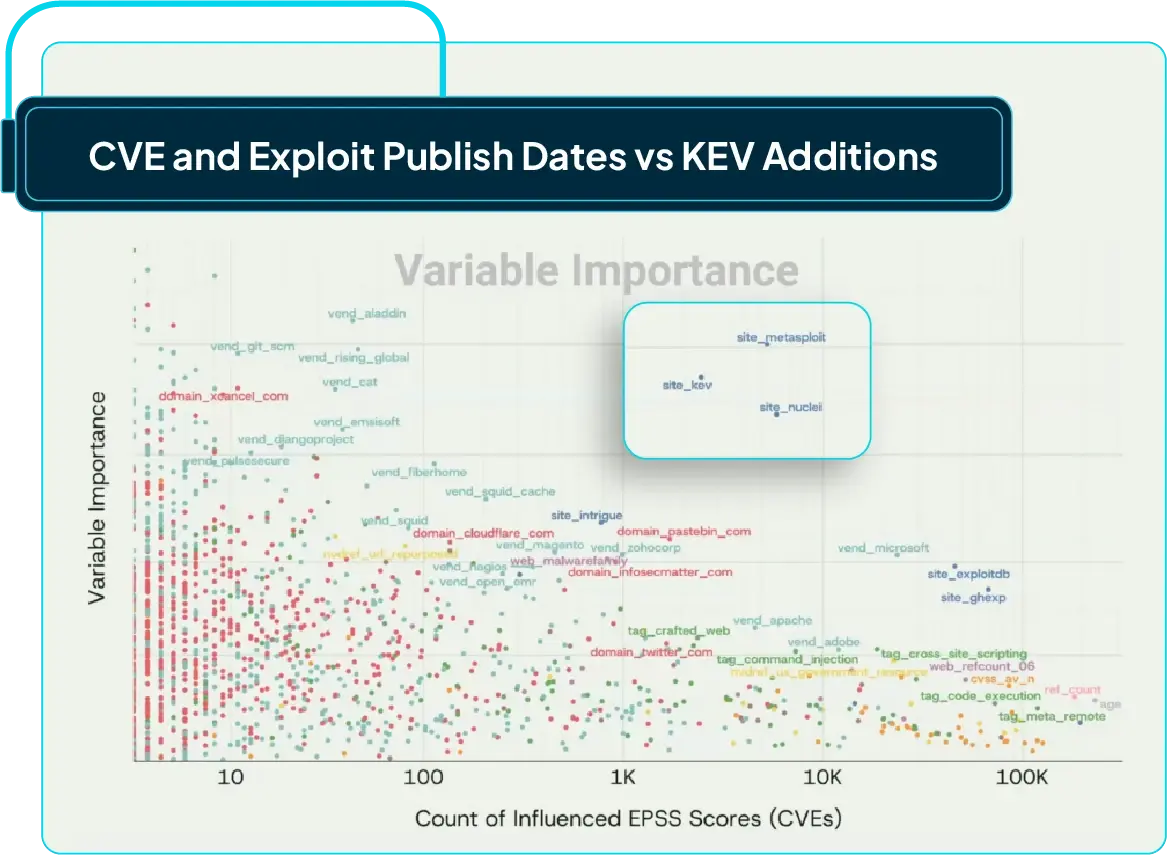

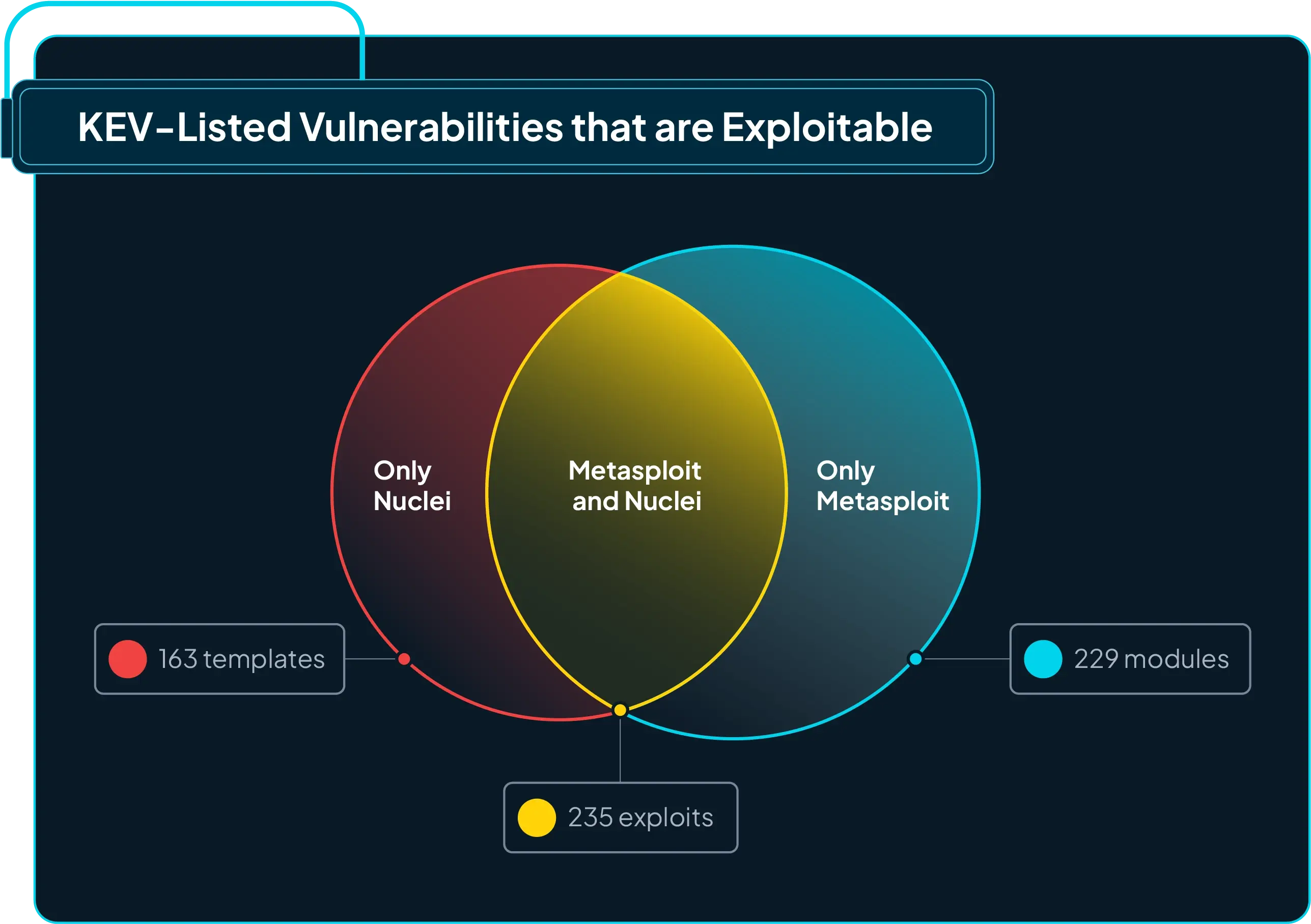

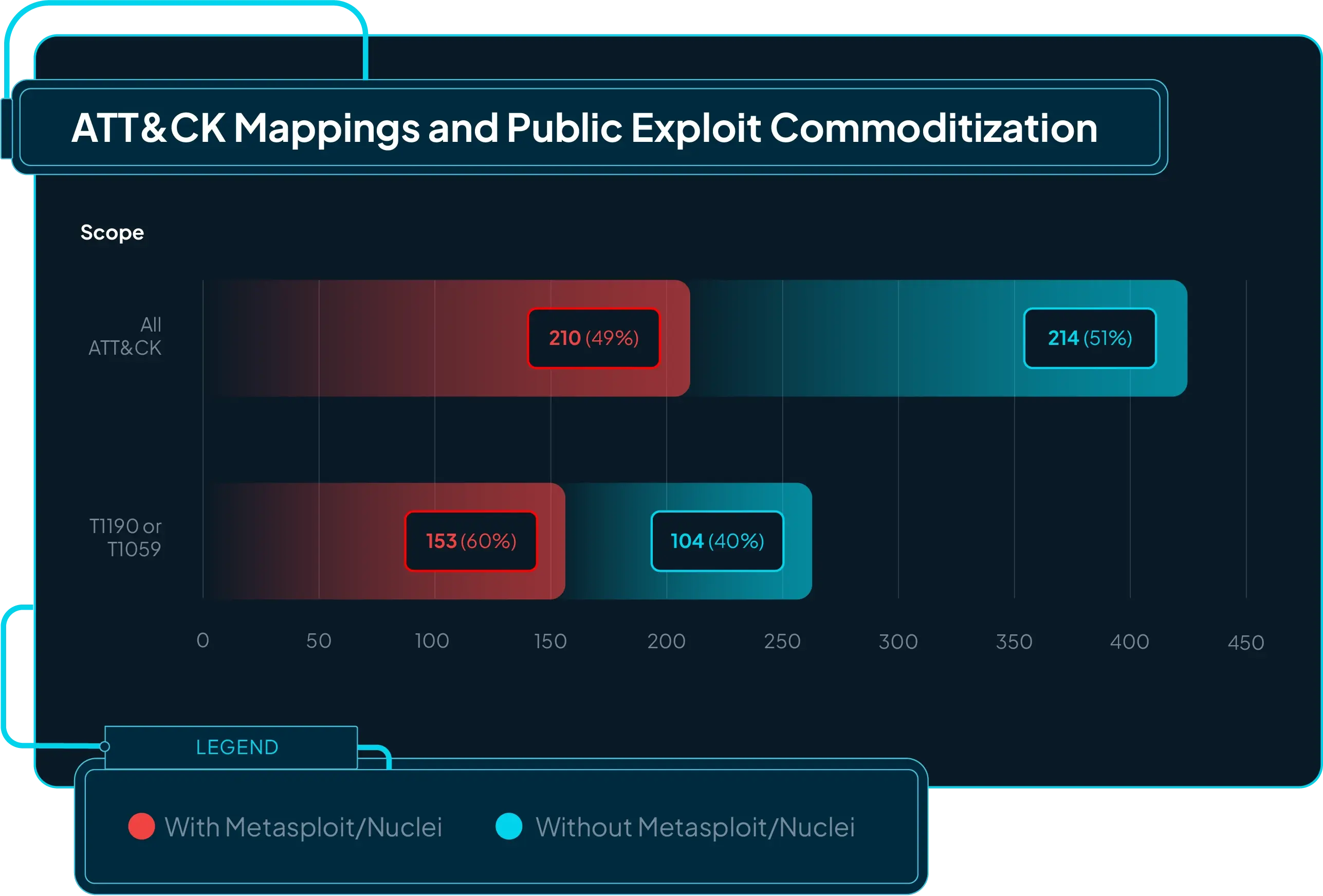

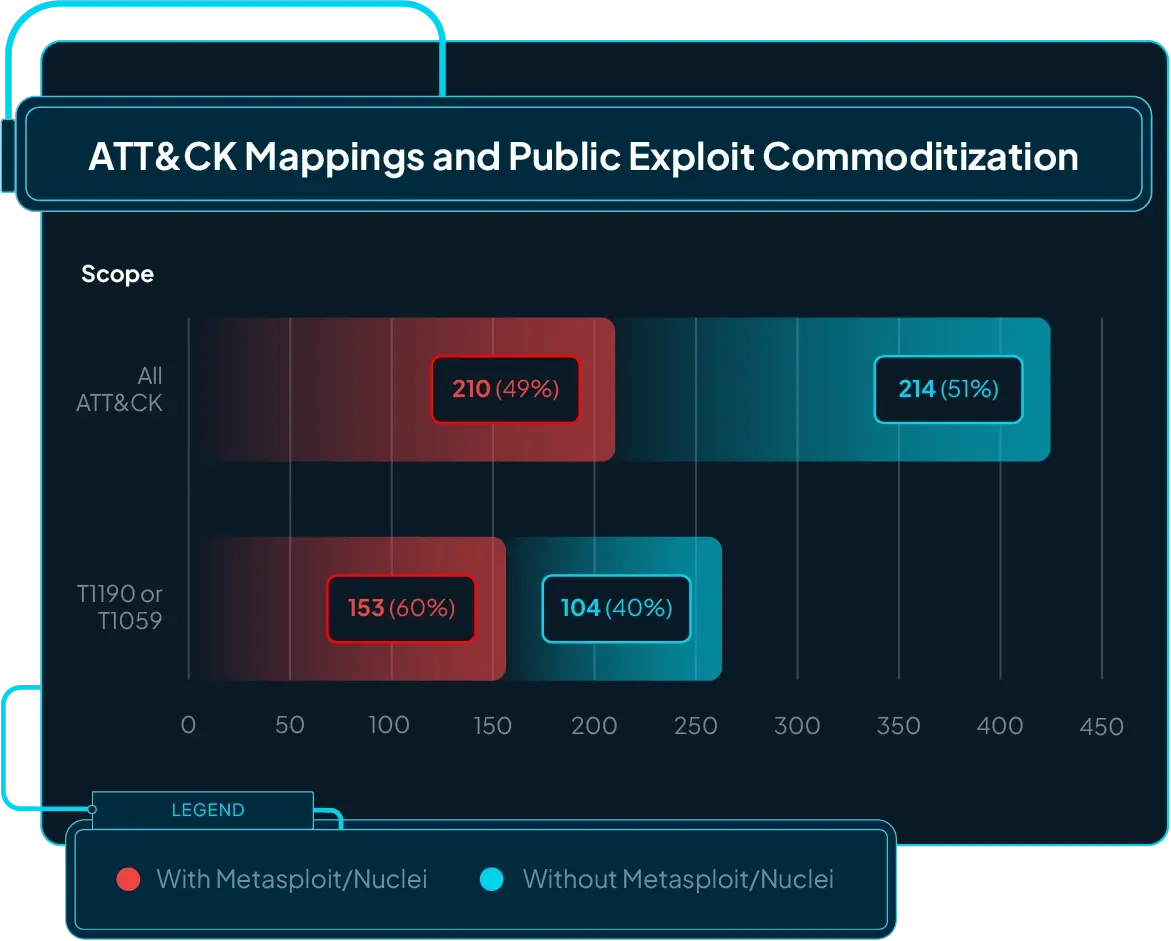

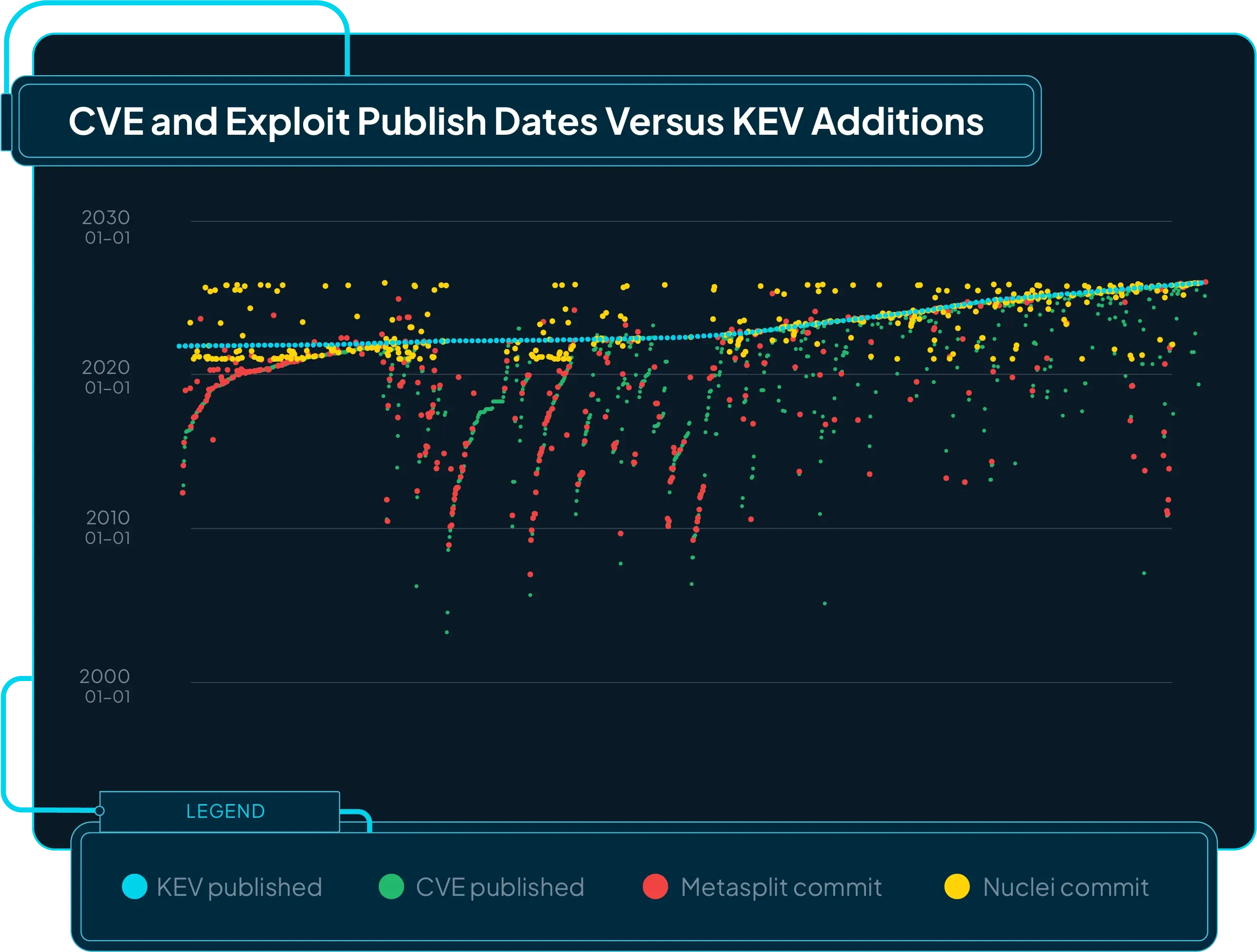

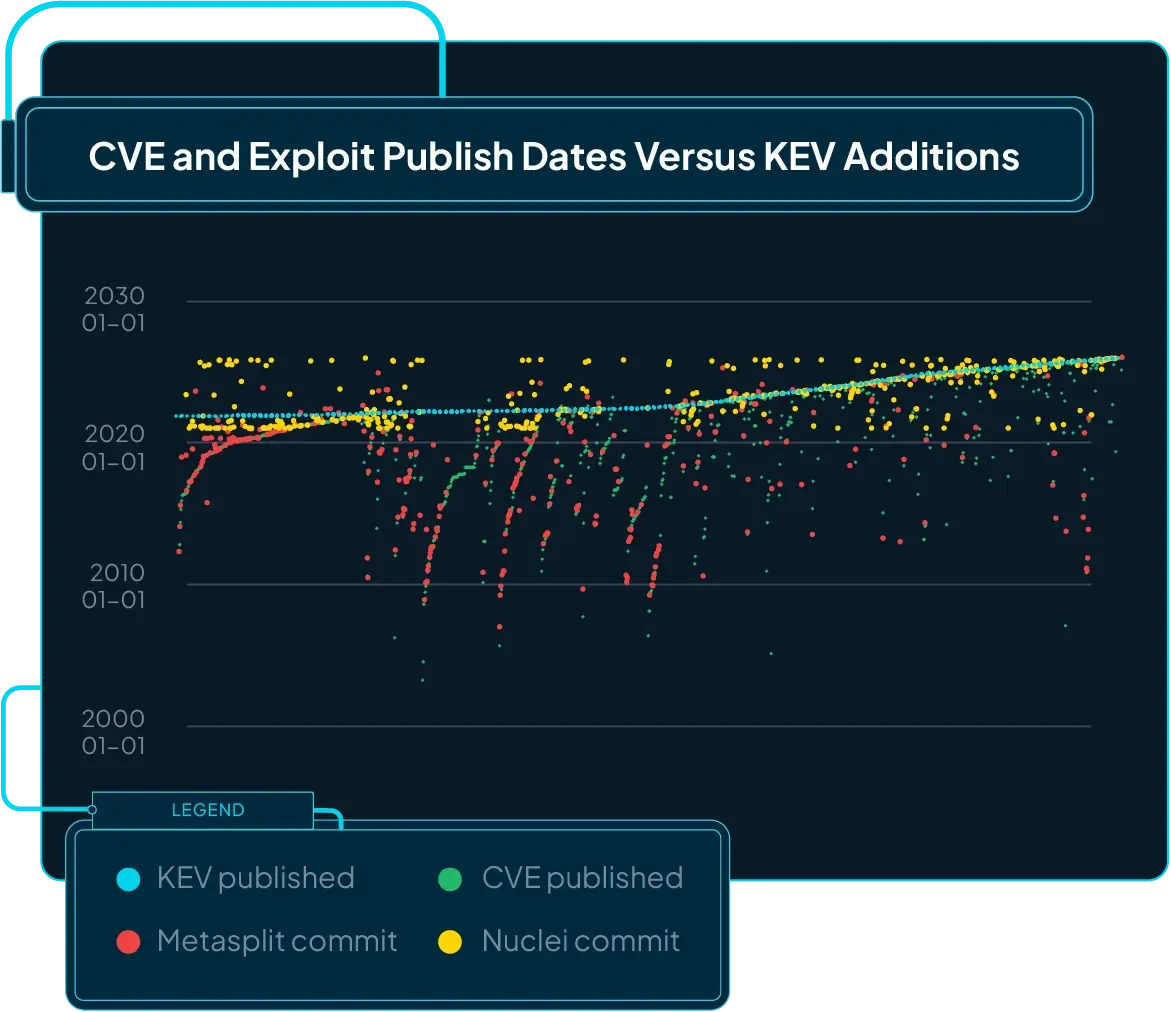

KEVology: an analysis of exploits, scores, & timelines on the CISA KEV

In the latest runZero research report former CISA KEV Section Chief Tod Beardsley, breaks down how KEV entries behave across exploits, scores, and timelines — and what actually matters for your environment.

-

Our Customers

Our customers are everything. We're super proud to be trusted by leading organizations around the globe to help them improve their security.

-

Case Studies

See how runZero has empowered security teams to take control of their networks, uncover their unknowns, and save significant time and money.

-

Testimonials

Read reviews of the runZero Platform and see how teams have improved their security with our technology.

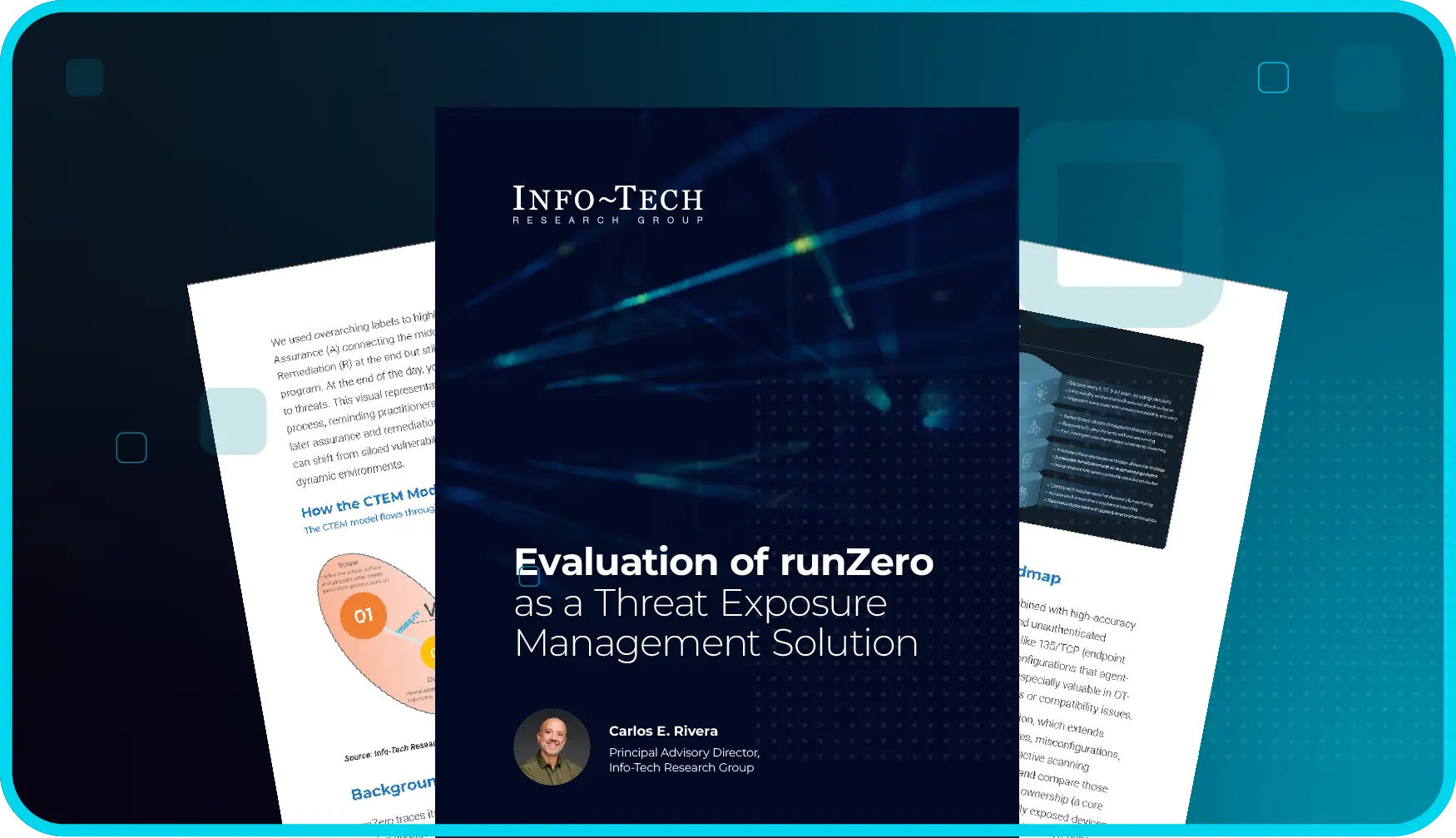

Info-Tech report confirms runZero as a leading CTEM solution

Info-Tech Research Group validates runZero as a reliable vendor solution for complex environments, highlighting its structured approach to CTEM, innovative agentless approach, and ability to detect full-spectrum exposure to deliver comprehensive visibility and rapid threat detection.

-

About Us

Wondering who the heck are these people? Meet the team and get the story behind runZero... once upon a time called Rumble.

-

Events

Track down runZero Yetis in the wild! Join us in-person or virtually at one of our upcoming events.

-

Investors

Meet the cybersecurity investors, trailblazers, and innovators who help us navigate our journey and the evolving security landscape.

-

Newsroom

Read the latest articles, announcements, and press releases from runZero.

-

Careers

Want to join our forces? We're looking for bright minds and passionate souls who want to write the next chapter in exposure management.

Join our livestream on March 25 for runZero Day at RSAC 2026!

That's right! We’re heading to San Francisco to sit down with a panel of experts to discuss the state of attack surface management. We’ll be breaking down everything from CVE dynamics to the reality of modern cybersecurity journalism and much more. The best part? No matter where you are, you’ve got a front-row seat.

-

Infinity Partner Program

See how we can work together to provide best-in-class security solutions and outcomes for our joint customers.

-

Partner Directory

Explore our directory of trusted (and awesome) partners.

-

Partner Sign In

Sign in to our Infinity Partner Portal.

Join our Infinity Partner Program

Designed with a partner-first mindset, the runZero Infinity Partner Program offers incredibly valuable resources, relationships, and rewards to partners who choose to grow their business with us.