Happy New Year, my vuln management friends! While I was busily scribbling on runZero’s next research paper, I became aware of a blog post from the CVE Council of Roots (a much less shadowy group than their name might lead you to believe). It’s all about the CVE Dispute process, what the dispute tag really means, and what the CVE Program does when there’s a disagreement about a particular CVE. This has been kind of a hot topic lately, what with the growing amount of CVE scope overlap that is the natural result of recruiting nearly 500 CNAs. Specifically, and unrelatedly, there was a bit of confusion over the recent React.js and Next.js bugs, and what all happened with one of those CVEs.

To get to the point, it occurred to me that I didn’t have an immediate understanding of how often CVEs are disputed, or rejected, in the first place. How big of a problem is this dispute and rejection confusion, really? That’s kind of a gap in my own understanding of the program, so since we’re talking about CVE disputes and rejections and all these sad outcomes for CVEs, let’s find out together how often this all happens!

First off, with over 300,000 CVE records currently published, it’s always a bit of a trick to count subsets of CVE records, especially when you’re dealing with CVEs that were rejected, and thus, deleted out of the history. CVE records don’t come with an easy and obvious history of changes – what you get today from a CVE record stands by itself, atomically. But, with just a little shell scripting magic and the power of GitHub, I think I have a pretty decent mechanism to keep on top of these stats, though it takes a few minutes to walk a git history.

Here’s my goofball shell script output, which depends on zsh, as I am a civilized gentleman on a MacBook for most of my computing. A run of this against a recent git checkout of CVEProject/cvelistV5 can shed some light on what actually goes on in CVE-land:

[2026-01-07 10:31:13] Completed audit:

[*] Total CVE records: 40480

[*] Rejected CVE records: 1648

[*] Year: 2025

1648 cveaudit-rejected.txt

120 cveaudit-disputed-today.txt

85 cveaudit-rejected-after-published.txt

18 cveaudit-rejected-after-disputed.txt

1545 cveaudit-rejected-unpublished.txt

3416 total

Some kind of interesting observations shake out here. First, CVE records are very rarely rejected these days. The CVE Program doesn't just swing, swing, swing the rejection hammer at every disagreement; out of the 40,000 CVE records created with a “2025” label, it looks like only 85 were rejected after they were first published. Most (about 96%) were caught and rejected before they ever saw the light of day, and that’s typically due to internal housekeeping – a CNA reserved a CVE, found out it was a duplicate, or not a bug after all, or some other internal process. No dramatic public fight or anything.

Even more interesting, of those CVEs that were published and subsequently labelled as disputed, for whatever reason, only 18 total (not 18%) were ultimately rejected. The comfortable majority (about 85%) live on, with the ignoble scarlet letter of a disputed tag.

Just in case you were thinking that 2025 was an outlier, it is, but not for the reasons you think. I get similar results for 2023. Kind of surprisingly, 2024 was the true outlier, since 2025 is a fair bit down from last year.

|

|

In all three years, the vast majority of rejected CVEs were never published to begin with. This lines up with the aforementioned blog from the CVE Council of Roots – the disputed tag is clearly not being treated as a death sentence for CVE records, but merely a signal that “hey, people disagree about this CVE record, and that’s okay.”

The surprising part, really, is how rarely disputed status even comes up. This could be explained a couple of ways. Maybe the dispute process is really, really high friction, so most people don’t bother unless they’re really annoyed by a CVE’s existence. Or, maybe there’s a nefarious conspiracy among the CNAs to squash dispute reports before they ever reach published CVEs, like some kind of Star Chamber of CVE truth. On the third hand, maybe most CVEs are basically okay, and there isn’t a need to over-engineer a dispute process when disputes are both rare, and meant to signal mild-to-severe disagreement over a CVE’s content.

What should you do with disputed CVEs? Well, since they’re so rarely disputed, they’re naturally going to be that much more interesting. After all, everyone secretly loves a liiiiitle bit of drama at work. You could study these all in the space of a few days, in depth, and hopefully come away with a better understanding of why they’re in dispute. If you are in a position where you need to justify to your manager why you are, or aren’t, addressing a particular CVE, and it’s disputed, you probably want to get a pretty good handle on what people are disagreeing on with that bug. But, since there aren’t hundreds and hundreds of these things, you can usually get caught up pretty quickly with just a little reference-spelunking. Ask the issuing CNA, or the original reporter of the vulnerability, and they’re likely to be eager to spill the tea.

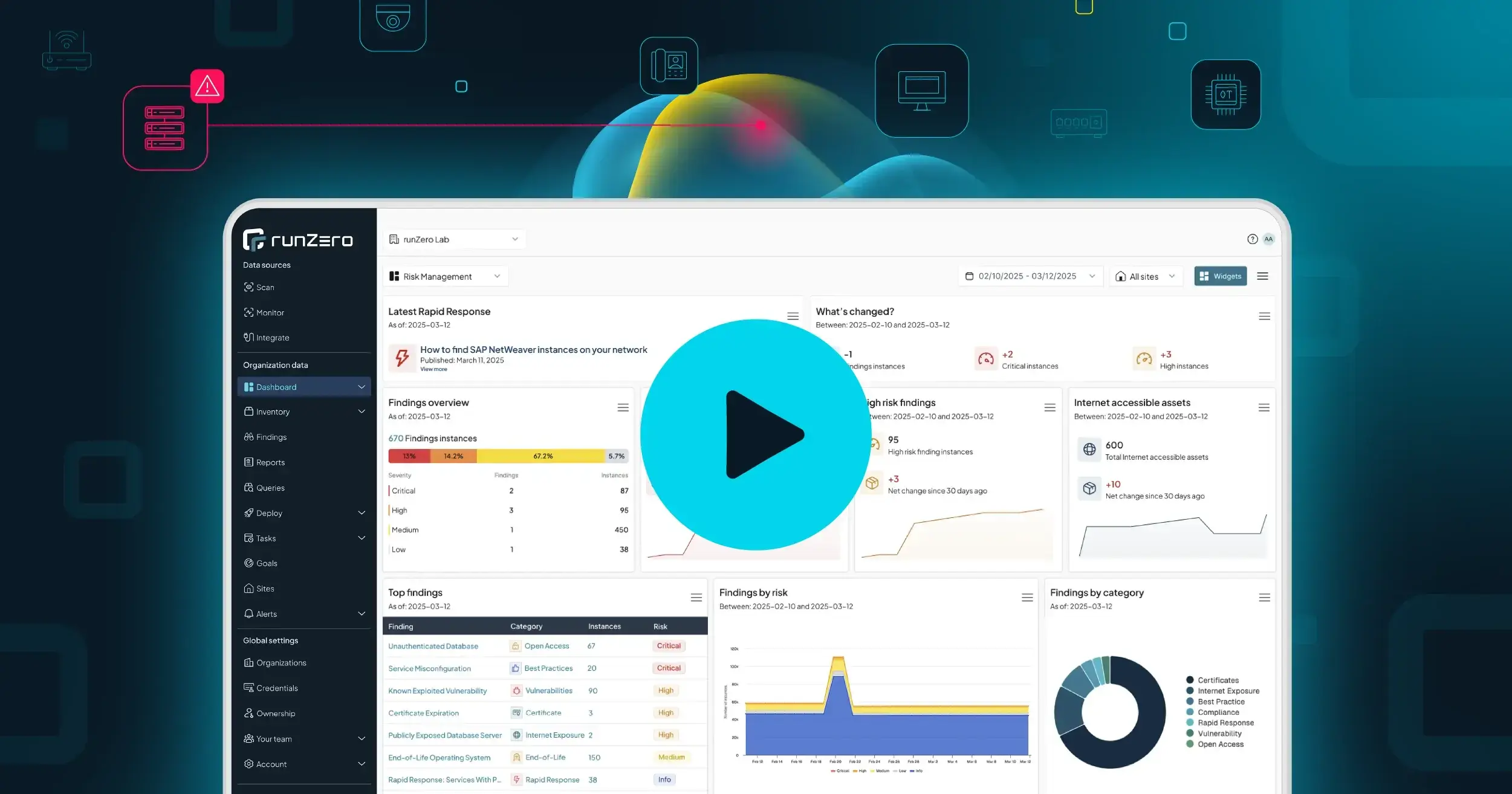

The moral of the story, though, is that while CVEs are generally useful for describing known, documented vulnerabilities, they are not the end-all, be-all of vulnerability management. There’s even a tiny percentage that aren’t themselves clear on if they’re even a vulnerability or not. As always, if you want to get a beyond-CVEs view of your enterprise’s overall exposure, in context, give our free trial a whirl, why don’t you? It’s 2026, a brand new year, and a fine time to consider a more whole-network, whole-exposure approach to vulnerability management that will actually help you not get hacked rather than just merely check the compliance box.